The Features of a Story

Long story short. A story needs a situation, tension, action, and result.

Several years ago, I was volunteering as a chaplain at a maximum-security prison in Nashville, Tennessee. Word came that the prison was going to implement a new “security” system that I knew would make life really difficult for some of the men I had befriended at that prison. So I accessed the prison volunteer database and emailed 250 people, beseeching them to inundate the Department of Corrections with protest calls and emails. And all our efforts did make the Department of Corrections take action, but it was not the action I hoped: they banned me from all Tennessee prisons.

The content of this story is true, by the way, but has nothing to do with this post except to illustrate the features of a story that I’m introducing. (I’ll get to that soon.) Last week, I wrote about a way of understanding stories that I learned from Marshall Ganz at Harvard: that is, stories contain challenges, choices, and outcomes. This week, I’m sharing another framework—STAR—because these forms can prove incredibly useful, especially if needing to put a story together on the spur of the moment.

From everything I’ve read, the “STAR model”—Situation, Task, Action, Result—was created as an interviewing tool so interviewees could quickly tell compelling stories when trying to get hired. And yet while the so-named model is somewhat new, the ideas behind it are very old. Personally, I don’t think the term “task” is the best word to use in this model, so I’m going to change it to “Tension.”

So, a story needs a situation, tension, action, and result. I’ll unpack each of these features of story below.

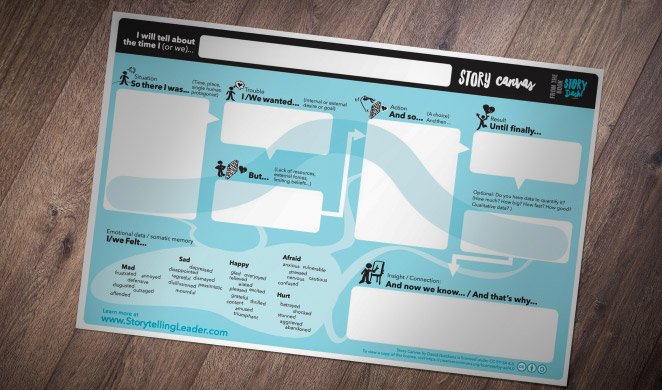

My colleague David Hutchens has an incredible resource he created based on the STAR model. Click the photo to hop over to his website and download it for free!

Situation (or Setting)

Stories always take place somewhere, some time, to someone. A place marker, a time marker, and a character are the immediate indications we are in a story. For the story to make sense, we have to know something about the context. What’s the situation? For instance, if I were to tell a story about a rocket launching into space, it wouldn’t be surprising if the setting was Florida in 2013. But if I started the story with, “About 1700 years ago, on a small island off the coast of Peru, a rocket left Earth…” then that setting is going to make a big difference to how you hear the rest of the story.

“A story is a pattern interrupted.”

Tension (or Conflict, or Challenge)

Every story has something that needs to be worked out. If everything were exactly the way it needs to be, there wouldn’t be a story. The great American novelist Margaret Atwood says a story is a “pattern interrupted.” Something normal or expected is happening, and then something not normal happens.

For example, I could tell you, “Yesterday, I woke up and went to work. I had my morning coffee as always, got to my meetings on time, finished my work, and came home to a delicious dinner, and then bed by 9.” You’d appropriately wonder, “What was the point of that story?”

But if I said, “Yesterday, I woke up and went to work. I grabbed my morning coffee as always, but before I could finish it, my colleague David burst in the door, eyes wide, grinning from ear to ear, and said, ‘Our proposal was accepted!’” Well, now, this is way more interesting. You are likely wanting to know what’s going to happen next, what the proposal was, who accepted it, and why it’s such a big deal. This desire to want to know more is a bedrock principle of good storytelling. And it’s all you really need to establish the tension.

Action (or Choice)

This is where the plot unfolds. When we say, “In a story, something is happening”—this is the happening part. When the pattern is interrupted, the character(s) in the story have to respond. How they respond moves the story along. We want to know what choices the character is making in the face of the challenge that arose. This is often the part in the story that goes like, “And then I… and so we… and still, they…” There’s a lot of doing happening here, moving us closer and closer to the end result.

Result (or Outcome)

Stories gotta end somewhere. Just like the plane I talked about before, you have to land the story. It can’t circle around in the sky forever. What happens as a result of all the actions, the choices made? Did the protagonist get what they wanted? Were they better off than expected? What happened in the end? Don’t be wishy-washy about this. Few things ruin a story like an unsure ending.

So, here’s a quick look back at the story I told at the start to see if it has all the features of a story:

Several years ago (Situation: time marker), I (Situation: character) was volunteering as a chaplain at a maximum-security prison (Situation: context marker) in Nashville, Tennessee (Situation: location marker). Word came that the prison was going to implement a new “security” system that I knew would make life really difficult for some of the men I had befriended at that prison (Tension/Challenge). So I accessed the prison volunteer database and emailed 250 people, beseeching them to inundate the Department of Corrections with protest calls and emails (Action/Choice). And all our efforts did make the Department of Corrections take action, but it was not the action I hoped for: they banned me from all Tennessee prisons (Result/Outcome).

This STAR model is an excellent framework to begin applying the key features of a story to the ones you want to tell. At first, try sticking to this particular order before trying to get too creative. As my friend Pádraig Ó Tuama once told me about poetry, “You have to learn the forms of poetry before you break them.” The same goes for storytelling.